“There's sometimes a tone of fear that people have going into their job search and a tone of anxiety and stress because of all the headlines around economic uncertainty, around the fiercely competitive market…. that’s across the board—from people who are at the executive level, middle management, all the way down to entry level.”

Sam DeMase, ZipRecruiter

I have seen similar concerns in my clients. What has changed in the last year, however, is that I’m seeing this anxiety in practically all my clients, even those who are happily employed. I hear profound worries about job security and long-term vocational obsolescence.

These worries can feel extremely threatening because there’s so much at stake when it comes to our work. For starters, 45% of US adults do not have three months emergency savings (according to the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve). Moreover, according to a Bankrate survey in 2024, nearly six in ten are uncomfortable with their level of emergency savings. It is unsurprising, therefore, that financial dependencies are often top of mind when it comes to job insecurity.

It is difficult to overstate the painful feelings of frustration, exhaustion and despair that a job search can engender. According to a survey of US adults in 2024, 72% of Americans say that applying for jobs feels like sending a résumé into a “black box.”

There is, nevertheless, a mindset change that can help people deal more effectively with job and career insecurity and turn it into opportunity: adopting a mindset that accepts and integrates the expectation of job impermanence. By accepting and reframing your job in this way, you can engage in activities that enhance your attractiveness to an employer (or a client) and avoid getting stuck in a more stagnant no-growth mindset. And if you can find the courage, consider transitioning to an anti-fragile mindset that views chaos as a catalyst for growth.A NOTE BEFORE CONTINUING

I had a great of deal of trouble writing this piece because I know how real the fear and pain of job loss can be. Sometimes it felt a little insensitive. Nevertheless, it is my hope that you can find something helpful to this piece as you consider job security and career advancement.

An Anti-Fragile Mindset

Nassim Nicholas Taleb wrote Antifragile: Things That Gain from Disorder in 2012 as an approach for dealing with “black swan” events. While somewhat controversial, this perspective can be applied to how we think about the risks associated with jobs and careers.

In the context of a job, here are some examples of situations that reinforce the impermanent nature of a job:

A strategic decision for the business to downsize.

Streamlining redundancies on the heels of a merger.

A change in prioritized skills due to changes in the market.

Performance issues.

An unhealthy relationship with a colleague e.g. the boss

The loss of a job for any of these reasons can occur as a random “unpredictable” event. But this is not the question since any prediction model is inherently imperfect. The actionable question for Taleb is what can be done to prepare for such an event: “You cannot say with any reliability that a certain remote event is more likely than another (unless you enjoy deceiving yourself), but you can state with a lot more confidence that an object or a structure is more fragile than another should a certain event happen.”

A more anti-fragile mindset —and there is certainly a spectrum between fragile and anti-fragile—accepts the impermanence of a job and embraces the benefits of engaging in activities that prepare for the moment when a job is eliminated or when you want to find a more desirable role. A more anti-fragile mindset also recognizes that the work done to prepare for chaos from job loss can actually fuel long term growth, which reduces fragility.

More Than Just Money

Certainly, employees are most aware of the financial hardship associated with job loss and even job stagnation. The loss of workplace health insurance magnifies this economic risk.

Money, however, is not the only benefit from work. As Carin-Isabel Knoop points out in her book on compassionate management, work offers us significantly more than money, and is a central building block of mental health. It gives us:

A social place to regularly interact with others.

Structure to shape the day.

A community to belong to.

A concrete social identity as a contributing member of society; and

A place to express and apply our values, interests, and creative energy.

Given these benefits along with the genuine economic dependence on the income, it is unsurprising that we can feel highly vulnerable to job loss; this vulnerability can lead to acute and chronic feelings of fear.

Today, these feelings of job insecurity seem particularly present. The rapid adoption and evolution of generative AI—a technology used to replace and augment human activities, and the increasing digitalization of the job application process —and the estimated 99% application rejection rate on major job platforms—are both likely suspects.

Job insecurity isn’t new: we know it can cause stress and trigger feelings of anxiety, anger, and even depression. These are our biological responses to the perceived threat, and they deplete energy. The emotions we may feel when this occurs—anxiety, depression, frustration, contempt—serve as alerts aimed to guide our response to the situation, albeit predictions (more on that below). These alerts, however, can block us from making objective assessments and a full accounting of the facts.

As a way of coping, we may construct our own personal narratives. These narratives originate from our well-intentioned brain that uses past experiences to predict the future and creates stories that help us make sense of our situation. These predictions are intended to guide us through perceived threats e.g. personal failure, lost social status, no income, etc. These can be quite inaccurate. and they can also limit our capacity to find viable solutions.

Let’s Look at Some Facts

The truth is that our employment has always been impermanent. What has changed, however, is the volume and the nature of the information reinforcing this reality. —so perhaps we are more frequently exposed to information that reminds us of the risks.

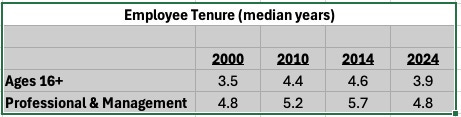

Here’s some historical employee tenure data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (the median number of years that wage and salary workers had been with their current employer). What you’ll notice in the table is that overall employee tenure last year was equal to or greater than in 2000 and about 8 months shorter than ten years ago. If the overall risk has risen (everything else equal), we might expect to see a significant decline in this number.

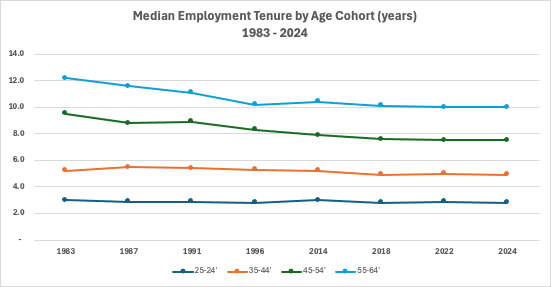

Let’s now consider trends in employee tenure by age cohort going back to 1983. Again, the trends don’t show dramatic declines in median employment tenure in any age cohort. While the 45-54 and 55-64 age cohorts do show about a 20% decline over the 40-year period, the younger cohorts remain relatively stable.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS)

Now let’s consider the mean duration of unemployment as a factor fueling job insecurity — how has that evolved in the last 40 years? Here’s the overall duration in weeks going back to 1984:

1984: 19.3 weeks

1994: 18.6 weeks

2004: 19.6 weeks

2014: 33.3 weeks

2024: 21.6 weeks

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS)

As you can see, while this data is sensitive to business cycles—the difference in job search duration can’t really explain the rising insecurity either.

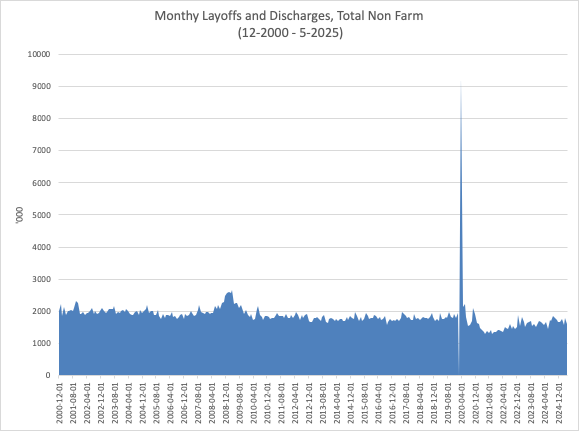

What about layoffs - has there been a jump in layoff activity in the last 25 years. As you can see in the chart below, apart from the start of Covid in March 2020, the trend in layoffs appears relatively stable and perhaps generally lower in the last 5-10 years, even if workforce and population increased.

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis

Despite these data trends, we know we can’t base projections of the future entirely on the past—is this time different? Perhaps it is the constant around AI, political and economic uncertainty, or social media negativity? No matter, we need to think about responses.

Framing Jobs as Impermanent

When we lose or fear losing a job, it can trigger many negative emotions. You know that if you lose your employment, you will no longer receive those direct deposits, you will no longer be a member of the team and prospects for growth will feel diminished. You may also view this as a personal failure.

Unfortunately, no matter who you are and where you work, there is no guarantee that your job will survive in the future. In the flash of a moment, as an employee at will, your job could be eliminated, or you could be asked to leave for performance. Fortunately, based on the data presented above, this does not happen very often in the life of an employee.

The truth is, you know intuitively that risk is probabilistic, and you make assessments on your situation in real time based on the information you collect.

For example, you might pay attention to:

How your boss, your peers, and upper management appreciate you

Whether you’re meeting performance objectives

How the group, division or company is performing

Which technology trends could impact you

How competitors are adapting, e.g., cost-cutting

The reality of employment impermanence —and resultant uncertainty it engenders about the future, influences how you make meaning of the stream of information you collect. But don’t shoot the messenger: the biggest challenge is choosing what to do with this information.

Maybe you were passed up for a promotion that went to a colleague. Or you’ve had the same title and done the same job for five years straight. When this happens, your level of stress and anxiety can heighten, and insignificant incidences can begin to validate a pessimistic narrative.

As the years pass, you may ask yourself hard questions related to your job security:

Why can’t I advance in my career?

How can I increase my impact?

What do I need to do to earn more money?

What job would make me feel more fulfilled and happier?

What to let go of

As you process the factors that impact your feelings of job security and growth opportunities, you also pay attention to the news and you wonder whether Armageddon is on the horizon. You’re inundated by emails and posts on social media about the impact of AI on a broad swath of professions, particularly knowledge workers and recent college graduates. You hear about layoffs in your industry or sector and forecasts of high inflation and recession. You wonder how vulnerable you are.

This information is real, and it shapes your predictions of the future and how your body responds with stress.

Unfortunately, you have no control of any of these forces. All of these forces—technology, economy, political—make up the environment in which you live.

What to grab onto

So what CAN YOU DO when the environment is challenging the status quo? This is not to say that the changes aren’t inconvenient or displeasing. At first, the feeling may be anchored in a fear of the unknown as Spencer Johnson describes in his “who moved my cheese.” parable involving mice.

Instead of clinging to feelings of fear, unfairness, and injustice, you can find the courage to act. Sure, some of these forces may gradually reduce the demand for people with your background and interests. True, the time to find a new role may be lengthened by a few weeks or months. Perhaps the promotion you were hoping to get may not come as fast as you expected last year.

But remember, you do have real strengths that got you to where you are today. You also have the opportunity to become even more by investing in yourself —that would represent an anti-fragile mindset. As a species, we humans have demonstrated over thousands of years our distinctive capacity to creatively adapt to changes.

If you can accept that all jobs are impermanent and transition toward a more anti-fragile mindset, you can mobilize your energy and gain more control. This means trying to incorporate personal growth into every job you have, with every boss you have, in every annual review you have. Many of my clients have figured this out and come to me for support.

So, what specifically are things you can control? Here are eight for you to consider:

Pay attention to your emotions: they are alerts your brain creates based on predictions of threats; in context of job insecurity, about the sustainability of your job and the consequences of losing it. However, it is essential to recognize the possibility of a cognitive distortion and actively listen for them. If you find your mind sounding more like a “tabloid” than rational enquirer, pause for a second. Your brain’s prediction is a best guess based on past experience—our brains treat any rustle as a threat, even when there is no snake. How you choose to engage with that feeling will make all the difference. Instead of collapsing into that negative feeling, let the information initiate an investigation into the facts:

Do they support your sense of higher risk?

How could you find more information to inform the risk of losing your job and what you can do about it? For example, scheduling a conversation with your boss to ensure you’re in synch or if there are gaps. Or analyzing the performance of the company and the trends you see in the industry.

Diversify the things that give you meaning. Searching for meaning and belonging in the workplace is a healthy pursuit; however, sometimes we can become over-invested in our work, and if this continues, we risk going from passion to pathos.

Separate the wheat from the chaff. Privilege your discerning mind. Retain what is valuable, discard what is not. THIS REPEATS A BIT Recognize your cognitive biases, including a tendency to look for information that confirms a narrative. Be curious about what you’re seeing, including the source. Challenge your conclusions by trying to prove the opposite.

Embed a detailed personal growth plan in every annual review with your boss that includes the development of new capabilities, relevant to your internal performance and your general competitiveness in the job market. This starts by understanding your role and expectations, what might be getting in your way to perform better, where you could contribute more, and strengthening skills that augment your impact. If you see an opportunity to modify the scope of your job, bring it up with your boss, If you’re overworked and you feel burnt out, let your boss know and brainstorm together how resolve the issue. If you’re certain you have a difficult relationship with your boss, consider strategies for improving it.

Create a 12-month skills expansion plan. Few of us have the knowledge to forecast the demand for jobs and skills. However, there are expert sources that can provide some guidance. Based on what you see yourself and what the experts suggest, consider strengthening areas that you think will be particularly important. For example, as technology automates many tasks, how will this affect the relative importance of emotional intelligence skills? What factors may change in your industry given changes in governmental policies or geopolitics?

Cultivate relationships with professionals in your area outside of your organization. This could mean a monthly lunch or coffee or ensuring you attend at least a couple of industry events per year. In a perfect world, you’d be doing this well before the “alert” because you accept and embrace the impermanence of your job and act accordingly.

Since you acknowledge the impermanence of a job and recognize it takes time to find a new job, build up a financial cushion to cover your cash flow needs. Moreover, add this fact into your decision making when choose any major expense items.

Hire a coach if you feel something is getting in your way and you need support in developing and executing your action plan. Work with the coach to clarify the strengths that will power you through any changes on the horizon.

The Art of Procrastination

With so much at stake, then, why do so many people say they don’t have enough time to prepare for the changes that may eliminate their job? Is it “procrastination?” Procrastination is generally viewed as a pejorative characteristic of “lazy” people.

In the case of job impermanence, the problem is not about putting things off; rather, it’s putting off the things that are exceptionally important. Putting off activities that have relatively little importance can be quite healthy and productive, particularly if it frees us up to focus on the things that matter the most to us. Author Oliver Burkeman make this point in his book 4000 Weeks: Time Management for Mortal. In it, he posits that a fear of failure may be the root cause of procrastinating what’s most important to us.

As you worry about the time and energy you have to prepare for the inevitable disappearance of your job, consider the other activities that have relatively little importance and reallocate to the ones that matter the most.

A Next Step

Any change you’re interested in exploring begins with assessing where you are now. If you believe your mindset and actions provide sufficient protection from the risk of job loss to calm your fears, there’s nothing to change. However, if you feel vulnerable to job loss in the short or long term, consider developing an independent plan—complemented with a workplace plan developed with your boss that includes a specific upskilling component. Independent of the workplace, consider creating a plan to diversify your life outside of work.

About the Author

David Ehrenthal is an Executive and Leadership Coach, Advisor, Confidant and a Principal of Mach10 Career & Leadership Coaching. David can be reached at dehrenthal@mach10career.com.